Recommendations: Ships' time in port is increasingly compressed, and the window period for dealing with PSC defects is extremely limited. However, there is a greater need to be composed under pressure. By systematically mastering the processing logic and closed-loop processes of defects, we can transform uncertainty into controllable operations. I hope this article will provide you with a clear guide to action, and when the next PSC inspector leaves the ship, you will be able to respond with confidence and calmness, regardless of the results of the report, ensuring that both the safety of the ship and the efficiency of its operation are ensured.

First of all, allow me to ask this question: are you sure that, during your term of office, ships will have a "zero defect" result every time they are subject to a port State surveillance inspection? If the answer is yes, then there may not be any need for you to continue reading this post. Because if the PSC defect is not detected, there will naturally be no need for subsequent processing.

However, you and I know very well that no one can be absolutely sure that there will be any deficiencies in the supervision and inspection of port States. Even if you serve the world's finest ships or the top shipping lines, there's no guarantee that a defect will never be issued in port state oversight. Take a step back and say that even if everything else is perfect, you may still receive a port state oversight flaw that you personally do not share. But that is not the core of the discussion in this paper, and the central question is this: what action should ship crews - especially shipmasters - take to avoid ship delays once port State oversight deficiencies are confirmed, and this issue lets explore that.

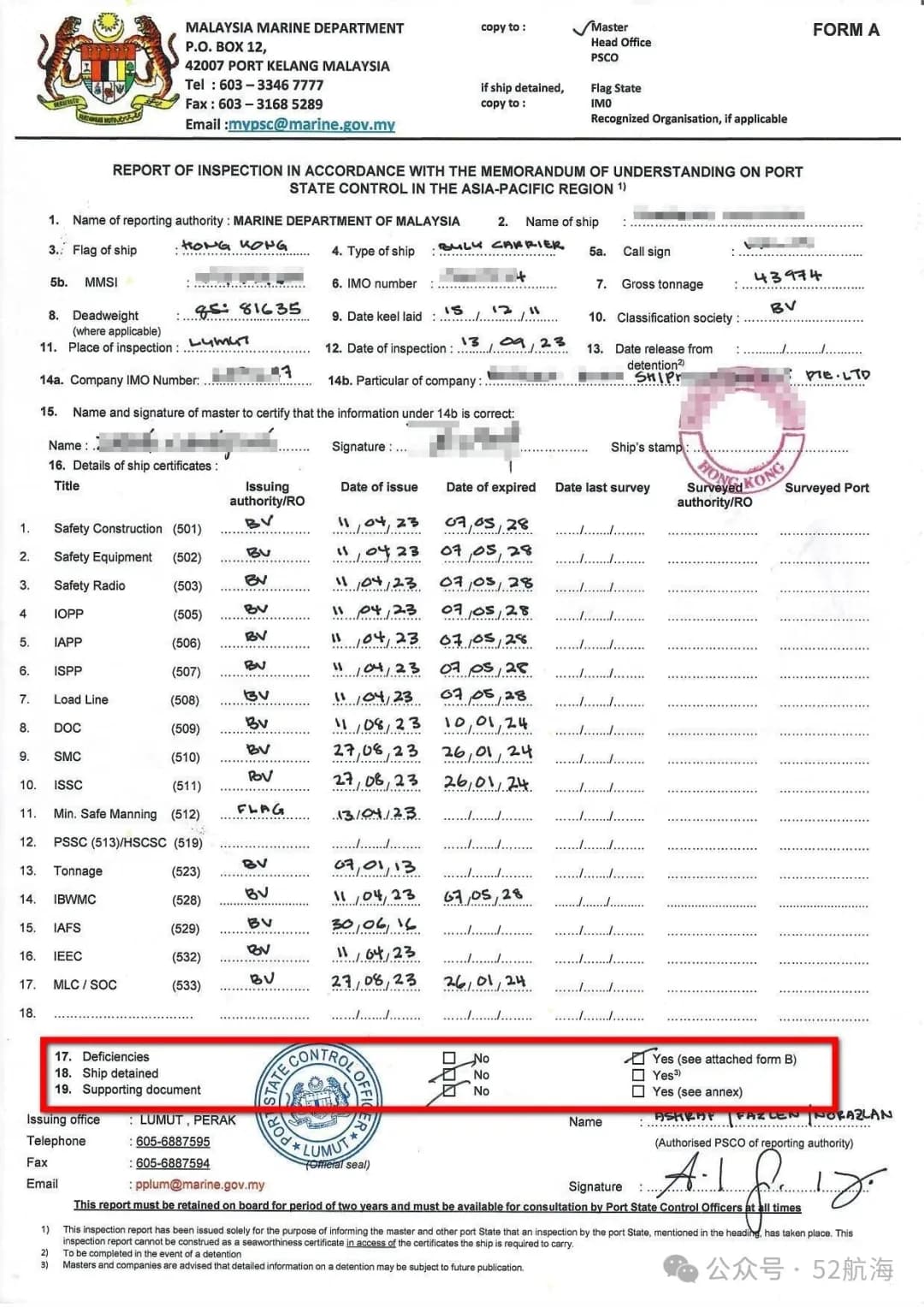

1. Interpretation of the report on the monitoring and inspection of port States

At the end of the port State surveillance inspection, a PSC inspection report is submitted to the master. Before signing a report, the captain must check at least three items carefully:

1). Ship name with date of inspection 2). All defects found during the inspection 3). Whether the vessel has been held up because of the defects found.

Although the information contained in the inspection reports issued by the different port State oversight memorandum of understanding organizations is largely consistent, their exact format may vary. Regardless of the format of the inspection report, the master must locate and verify the accuracy of all three items of information in the report.

2. Non-defective port State surveillance reports

What could be more gratifying than to complete a single port State surveillance inspection with a "zero-defect" result? After obtaining a non-defective port State supervision and inspection report, the master is required to properly preserve the report in accordance with the company's document filing system.

The master may also deposit a scan of the inspection report in the vessel's electronic planned maintenance system.

If the company subscribes to the Q88 service, it would be wise for the captain to update the date of this port State surveillance inspection in the Q88 database in good time.

Even if the inspection results in zero defects, the master must inform the shore-based management company of this port State supervision inspection.

In addition to that, for this check, no other action is needed.

3. Defective port State surveillance reports

If a port State surveillance inspection reveals a defect, the column "Defects" of Form A in the report will check "Yes".

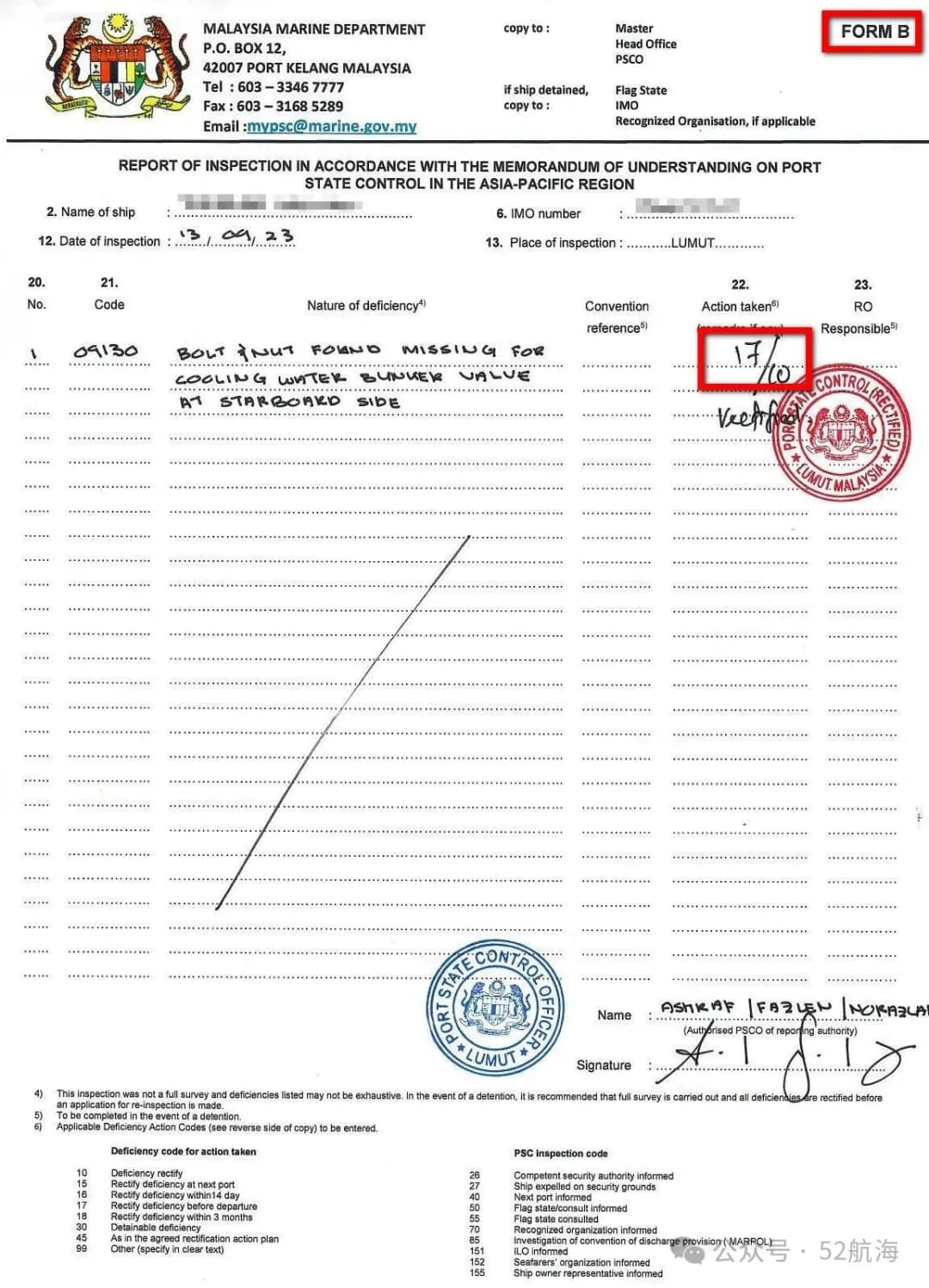

All identified defects will be described in detail in Form B, which is attached to "Form A". In Form B of the Port State Surveillance Inspection Report, each listed defect will correspond to an action code.

Each flaw may correspond to one or more of the following action codes:

Deficiency code for action taken Code 10 - Deficiency rectify 15 - Rectify failure at next port 16 - Rectify failure within 14 days 17 - Rectify failure before departure 18 - Rectify failure within 3 months 30 - Detainable deficiency 45 - As in the agreed rectification action plan 99 - Other (specify in clear text)

PSC inspection code Code 26 - Competent security authority informed 27 - Ship exploded on security grounds 40 - Next port informed 50 - Flag state/consul informed 55 - Flag state consulted 70 - Recognized organization informed 85 - Investigation of convention violation discharge provision (MARPOL) 151 - ILO informed 152 - Seafarers' organization informed 155 - Ship owner representative informed

4. Correction of deficiencies

I have always maintained that it is more difficult to detect defects than to correct them. Therefore, once a flaw has been identified, correcting it shouldn’t usually be difficult. But the point is, who will confirm that the defect referred to has been rectified? Is it sufficient to rely solely on the captain's statement that "the defect has been rectified"? Do port State supervisory inspectors need to board the ship again to verify the correction? Or does it require a classification society to verify the repair of the defect?

In practice, it depends on several factors:

Specific port State supervisory authorities and/or the port State supervisory MoU organisation to which they belong

Nature of the defect and the field to which it belongs

For most deficiencies, for example, the United States Coast Guard requires verification by the classification society that they have been corrected. My experience in Russian ports is that port State supervisory inspectors carry out re-inspections to confirm that defects have been closed. And in most Chinese ports, a written statement from the captain is generally considered sufficient to close most defects.

In general, all defects related to the machinery and structure of the vessel, the closure needs to be confirmed by the classification society of the vessel. In such cases, the classification society imposes a "Condition of Class" on the vessel, which is lifted after the defect has been corrected.

Given that deficiencies may be closed differently by different port State supervisory authorities, it is prudent for the master to clarify the confirmation on his own initiative with the port State supervisory inspector.

5. Treatment of deficiencies in port State supervision as Non-conformities

Management procedures in most companies require that any port State oversight deficiencies must be dealt with as non-conformities.

Port State oversight deficiencies must be dealt with following the procedures established by the company for non-conformities.

According to the Safety Management System Manual, the procedure for closing deficiencies in port State supervision is the same as the procedure for closing any other non-conformities.

In the case of tankers, the treatment of port State surveillance opinions as non-conformities is a mandatory requirement in accordance with the SIRE requirements.

6. Code 17 Defects

Code 17 defects are the most common type of defect in port State surveillance inspections. All defects with code 17 must be corrected before the ship departs port.

The most common question here is: Does port State supervision require re-embarkation to verify that code 17 deficiencies have been corrected?

Some ports may require review verification, while others may not require this step.

The master of the vessel must make clear to the port State supervisory inspector the need for re-verification.

In the event of re-verification, the master shall promptly notify the port State supervision through an agent after the deficiencies have been corrected.

After passing the recheck, the master must ensure that all code 17 defects are marked on the report as code 10, indicating that the defects have been corrected.

It is essential that any code 17 deficiencies are remedied before the ship leaves port, regardless of whether port State oversight requires a review of the closure. Vessels that leave port without correction of code 17 deficiency are considered unseaworthy. Taking an unseaworthy vessel to sea can have serious consequences for the captain.

It is good practice to send an e-mail to the port State supervisor through a proxy formally informing that the defect has been corrected, if the port State supervisor does not require a review of the defect closure.

7. Defects other than code 17

Code 17 deficiency requires immediate action and must be closed before departure. But for defects in other codes, such as code 15 (correction before departure from the next port) or code 18 (correction within 3 months), the situation is different. Although the corrective deadlines given for each defect vary, their treatment flow is similar.

For example, for a code 15 defect, the master must send a defect closure acknowledgement prior to departure from the next port. Alternatively, if a port State supervisory inspector is required to verify the defective closure in person, the request must be made by reserving sufficient time by the agent.

8. Retainable defects

The detentionable defect is of a serious nature, so its closure process is also different from other defects. A common perplexity is how to distinguish a code 17 defect from a stayable defect. For example, is "SART not working search and rescue radar transponder not working" a code 17 defect or a stayable defect?

In practice, the fine line that separates code 17 defects from detentionable defects is not difficult to discern for experienced port State surveillance officials. The procedure for determining whether it is a detentionable defect is clearly specified in the inspectors' manuals organized by each port State to supervise the memorandum of understanding.

For example, the Paris MOU provides the following main criteria for an inspector to determine a ship is stranded:

Ships which are unsafe to proceed to sea will be detained upon the first inspection respective of the time the ship will stay in port. If, after inspection, it is established that the vessel would pose a danger if it sailed to sea, it will be detained at the time of the first inspection, regardless of the length of its stay in port;

The ship will be retained if the qualifications on a ship are sufficiently serious to merit a PSCO returning to the ship to be satisfied that they have been corrected before the ship sails. If the defects present on the vessel are so serious that the inspector deems it necessary to board the vessel again before the vessel sails to confirm that the defects have been rectified, the vessel will be held up.

The Port State Surveillance Inspector's Manual of the Paris Memorandum of Understanding further enumerates areas of deficiencies that may constitute a basis for detention.

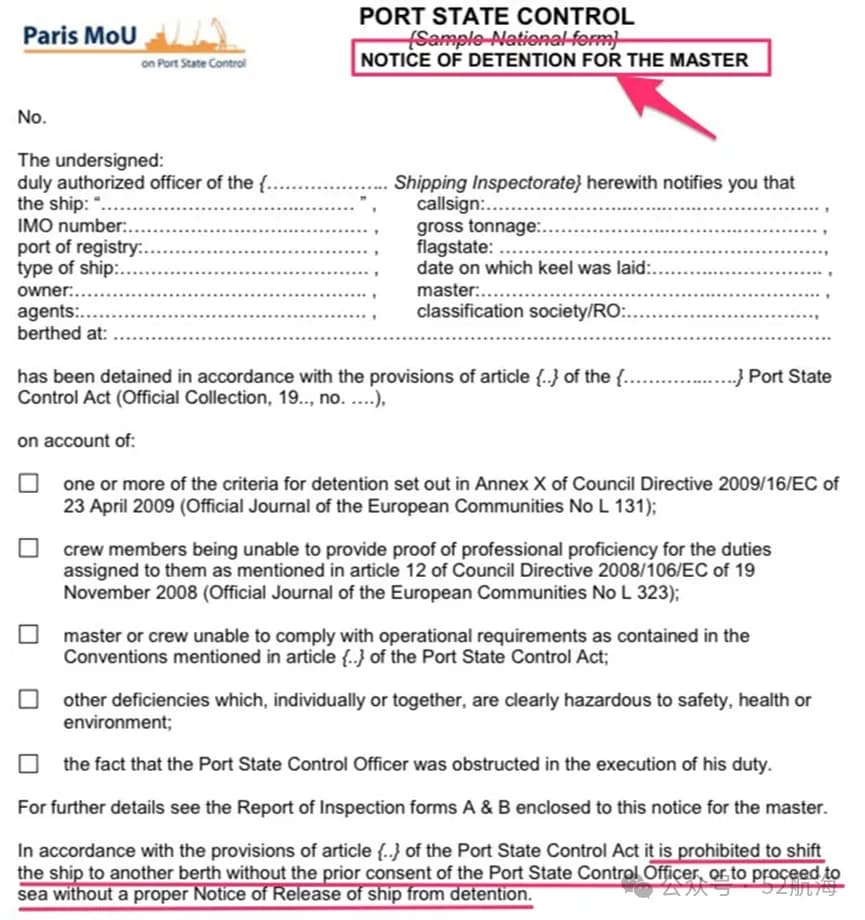

9. Ship-detention procedures

If the port state surveillance inspector decides to detain the ship, they issue it to the master " Notice of Detention ".

At the same time, the port State supervisory and inspection officer will also copy the detention notice to the competent authorities of the flag State of the vessel and the classification society of the vessel.

Most flag Governments require that if a ship is held up by any port State supervision, the master/company must report to it.

The master is required to confirm with the company whether the flag State needs to be notified directly by the ship.

10. Grievance procedure and Retention Procedure

If the master/company considers that the vessel has been unreasonably stranded, the company may submit a complaint to the port State supervisory authority. If the owner or operator of the vessel does not wish to use the formal national complaint procedure but nevertheless wishes to contest the detention decision, such complaints shall be sent to the flag State or to a recognised organisation issuing the statutory certificate on behalf of the flag State. The different port State supervisory authorities have different grievance procedures, which are available on their official websites or through port agents.

For example, the Paris MoU Paris Memorandum grievance procedure looks like this:

Official Website: https://parismou.org/PMoU-Procedures/appeal-procedure

Appeal procedure National appeal

When deficiencies are found which render the ship unfit to proceed or that poses an unreasonable risk to the environment, the ship will be detained. The PSCO will issue a notice of detention to the master. The PSCO will inform the master that the ship’s owner/operator has the right of appeal.

Appeal notice details can be found on the reverse side of the notice of the detention form and are various in the Paris member States.

Detention review procedure

In case an owner or operator declines to use the official National appeal procedure but still wishes to complain about a detention decision, such a complaint should be sent to the flag State or the Recognized Organization, which issued the statutory Certificates on behalf of the flag State.

The flag State or R.O. may then ask the port State to reconsider its decision to detain the ship.

If the flag State or the R.O. disagrees with the outcome of the investigation as mentioned above, a request for review may be sent to the Paris MOU Secretariat.

The establishment of a grievance procedure is reasonable and necessary. Once a ship is stranded, it will seriously affect its operation, as charterers are generally reluctant to charter a ship with a recent record of being stranded. Even if a charterer can be found, the freight rate is often low because of the reduced bargaining power of the ship. In addition, the company will suffer a blow to its brand image. Most port state oversight memorandum of understanding organizations publicly disclose lists of underperforming ships and companies on their official websites.

Finally, the detention of a ship can also affect the performance of its flag State, possibly resulting in the flag State being placed on the "Grey List" or the "Black List".

Given the significant interest involved in the detention incident, it is always worth considering initiating a grievance procedure if the master, company or flag State is satisfied that the detention decision is not justified. The grounds of the complaint are not necessarily objections to the deficiencies themselves. If the shipowner or the flag State considers that the severity of the defect should be classified only as a code 17 defect (to be corrected before sailing) and not as a detentionable defect, it may likewise lodge a complaint.

There have been cases, for example, where flag States have contested ship detention decisions.

11. Closing retention defects

After all the necessary notification procedures have been completed, the next priority is to proceed as soon as possible to close the defects causing the detention in order to minimise the loss of ship time.

The first step is to understand the defect term accurately. We must not misinterpret defective content and thus waste our energies on irrelevant aspects.

For example, if the defect relates to the MARPOL Convention, we need to be clear, whether the defect refers to a malfunction of the equipment, or to a problem related to a certificate or document.

It is assumed that the defect relates to the "enhanced inspection procedure" and that the defect code given by the port State supervision is 01311.

Code 013 points explicitly to certificates and files. Our efforts should therefore focus on obtaining missing documents, or contacting the flag State/classification society, as the case may be, to correct the errors noted in the documents.

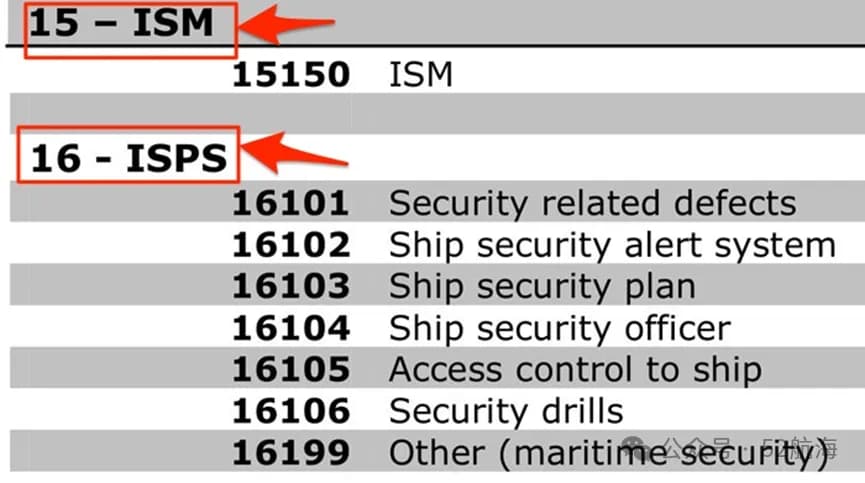

Another case that requires special attention is the detention defect involving ISM & ISPS rules. Because Retention caused by defects related to ISM & ISPS rules must be passed externally ISM & ISPS After the review, it can be lifted.

Again, these flaws can be identified by their specific code.

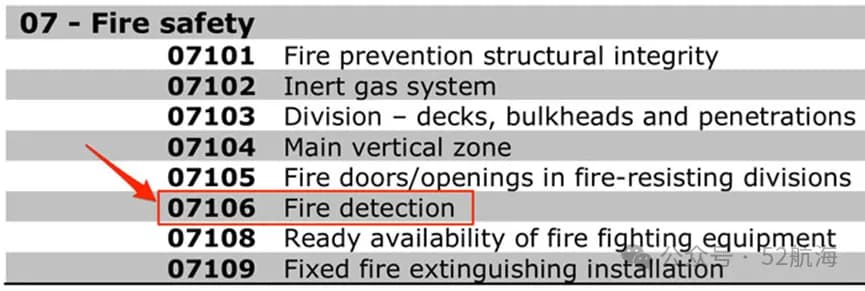

A further elucidation of the detentionable defects associated with ISM is provided with an example. There is sometimes a misconception that the shortcomings relating to the ISM rules must be those in terms of instruments or documents, which is not always the case. Take, for example, the flaw in a fire detector failure in a living area: one fire detector failed and was usually listed as a code 17 flaw. The defect is classified under code 07106 and is to be corrected before sailing.

Whereas the simultaneous failure of two or more fire detectors may constitute, at the professional discretion of the port State supervisory inspector, a detentionable defect, which is likewise classified under code 07106. Since the ship will be detained, the inspector boards the ship to verify that the fire detector has been repaired. The detention order will be revoked and the ship allowed to sail after the inspector confirms that the issue has been resolved.

Now consider a more serious scenario: assume that ten or more fire detectors are found to be disabled. This would undoubtedly constitute a stayable defect under code 07106. But this situation at the same time sends a signal to the port State supervisory inspectors that the ISM rules may not operate effectively on board. How to see?

Because if the safety management system operates efficiently, these faulty detectors should rightly be detected in the most recent weekly/monthly tests and reported for repair in a timely manner. Such a large area of failure indicates that the vessel failed to perform regular routine inspections and maintenance as required by the safety management system.

In such cases, the port State supervisory inspector will most likely write out a second detentionable defect, pointing directly to the effectiveness of international safety management rules, which may be described as follows:

"The ISM code is not effectively implemented as apparently no weekly checks on the fire detectors are being carried out. International safety management rules are not effectively implemented, and the evidence suggests that weekly inspections of fire detectors were not performed as required by the system."

Thus, one equipment failure watch can trigger two trapable defects. As mentioned earlier, deficiencies related to non-international safety management rules can be closed by correcting the problems indicated. However, deficiencies related to international safety management rules must be closed after the flag State or its authorized classification society has completed an external audit and confirmed that they are qualified.

Conclusion: In recent years, the duration of ship stays in port has been considerably reduced, which leaves the crew with extremely limited time to deal with deficiencies identified by port State surveillance inspections. However, if we can have a clear grasp of the correct methods and processes for dealing with deficiencies in port State supervision, we can effectively save time and avoid to the greatest extent possible delays in shipping schedules that may result from untimely closure of deficiencies.

This guide on Jebel Ali Port is a rare and practical “field manual.”

It avoids empty theory and instead focuses on detailed, firsthand experiences and lessons learned from captains and crew. The article not only summarizes standard operating procedures but also reveals the unwritten rules and potential extortion risks during port inspections — along with concrete countermeasures and reliable information.

Whether you are a newcomer calling at this port for the first time or an experienced master seeking to optimize your operations, this article is highly valuable and worth saving.

I. Communication and Pilotage

1. General: Jebel Ali is a large international transshipment port with many terminals, usually direct berthing. The Pilot Station is 30 nautical miles away. Contact Port Control via VHF Channel 69 to request pilotage. They will inform you when and where (e.g., “XXXX time at Buoy XX”) to take the pilot. The pilot boards on the north side of the channel; vessels must not enter the channel before the pilot embarks. For deep-draft or fully loaded ships, pilots board at the channel entrance.

2. Pilotage Details: Port Control will guide you before pilot boarding. Pilots come from various countries — competent, professional, and polite; no one asks for gifts. Pilot boats are modern and fast; pilot ladder position: 2 meters above waterline. Tugs are modern and maneuverable, positioned before the breakwater and use towing lines properly.

3. Light-Draft Vessels: Vessels with shallow drafts also embark/disembark pilots on the north side of the channel. Multiple ships may operate simultaneously — coordinate carefully.

4. Current: Crosscurrents are generally weak, typically under 1 knot, confirmed with pilots during experience exchanges.

5. Buoys 7–9 Area: Charts may show uncertain depth marks or separation lines — pilots say these are meaningless, and ships routinely pass without issue.

6. Caution: When waiting outside the channel for pilot boarding, outgoing ships may suddenly turn right and exit — ensure proper coordination.

7. Departure Pilot: Pilots board from the shore side, disembarking just after clearing the breakwater. You can negotiate slightly earlier or later departures with the pilot.

II. Pre-Arrival Documents and Port Entry Procedures

1. Important Note: The last port clearance must clearly state JEBEL ALI PORT, U.A.E. (Make sure to inform the previous port agent in advance.)

2. HA Border Security – Crew List Form: A tricky form; best to get a sample from your local agent. Fill in the following: TYPE: C BATCH: APP DIRECTION: I VESSEL: IMO Number Departure Port: previous port code Arrival Port: AEJEA (code for Jebel Ali) Column D (Document Sub-Type): Captain = “M”, Crew = “S” Column M (Travel Type): All “N” Usually, the agent fills and submits it, so you can just send your version — not critical.

3. Required on Arrival: - All crew Seaman’s Books and Passports - Port Clearance from the previous port (if electronic, print in color) - Certificate of Registry - Crew List (special Jebel Ali format) - A simple form filled on-site

4. “Emergency & Pollution Letter” Issued by the agent — includes current onboard quantities. All items except bunker figures should be pre-filled. Pilots need these figures before berthing.

5. Personal Items: No restrictions on personal tobacco or alcohol; bonded stores remain unsealed.

6. Procedures: Very straightforward — only need seaman books, passports, clearance, crew list, and registry copy.

7. Shipboard Agent: A resident agent will stay onboard to handle discharge, documentation, etc. — similar to a loading master.

8. Departure Procedure: Managed by the resident agent. Usually completed within 10 minutes after cargo completion (since the departure clearance is pre-arranged). Obtain the departure clearance number before calling Port Control for “All ready for sailing.” Sometimes pilots are delayed — examples include 1–2 hour delays. If pilot boarding is late, remind Port Control every hour.

9. Departure Documents: The agent emails the necessary departure documents. Simply modify the arrival forms to “departure” status and update times. Always check email promptly — failure to submit 24 hours in advance can delay departure.

III. Cargo Discharge Operations

1. General: Shore labor is efficient and well-organized; port machinery is abundant. Cargo is unloaded directly to yard by forklift. However, lighting requirements are strict — minimum 4 deck lights per hold, sometimes 6, or they stop work. If cranes trip or power fails, stevedores wait silently — be alert. No dedicated safety officers wandering around trying to find faults.

2. Incidents: Some damaged steel sheets slid between cargo gaps; stevedores refused to unload, and crew had to manually retrieve them. For deck cargo extending beyond hatch coamings, must be discharged first and reloaded after cargo completion. Captain must email a written statement (e.g., “Any damage during reloading not ship’s responsibility”). Resident agent promptly reports serious damages; minor damages may only appear in post-operation reports for chief officer confirmation.

3. Surveillance: Tall lighting towers equipped with HD cameras; all activity monitored. Anything not permitted must be formally requested and approved — don’t act without permission.

IV. PSC-Type Inspections (Port Safety Checks)

1. Repairs: Any onboard repair (e.g., radio, machinery) must be pre-approved through the agent. “Port Safety Inspectors” can be troublesome — extortion is common. For example, a radio repair done during office hours led to a $400 bribe demand in 2018 for lack of prior notice.

2. System and Fines: Similar to PSC (Port State Control). Detected deficiencies result in fines imposed on the agent, who then recovers them from the shipowner. Re-inspection fees also apply. Reports are emailed instantly to the agent and copied to the vessel. Without clearance of deficiencies, the departure permit will not be issued.

Example: In 2020, an inspector arrived two hours before sailing, demanded $300, settled for $200. The inspector had previously served as 3/O, C/O, and with a classification society — capable of finding serious issues if resisted. Detentions can cost up to $10,000 to “resolve.”

3. Other Experiences: One vessel was checked for ID cards, engine room helmets, garbage and oil record books — no bribes demanded. Another vessel fined $4,000 for “black smoke from funnel.” Local officials sometimes invent fines; failure to pay means no departure clearance. Attempts to dispute often lead to even higher penalties.

V. Miscellaneous

1. Shore Leave: Tours and shopping in Dubai can still be arranged through the agent. Official shore pass: USD 100 per person; unofficial/private: USD 50 each.

2. Communication: Mobile network signals in the port are decent.

3. Flag Etiquette: The UAE national flag should be raised during the day and lowered at night.

Source: Captain's Experience Date: October 6, 2025

Let's say for example, a tanker calling at Fujairah, when does an agency typically begin pre-arrival work — is it days before or only after NOR submission?